Catalan language

| Catalan, Valencian | ||

|---|---|---|

| Català, Valencià | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | 9.8 million | |

| Ranking | 93 | |

| Language family | Indo-European | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | In Spain: Catalonia, Valencian Community, Balearic Islands. In Andorra. |

|

| Regulated by | Institut d'Estudis Catalans Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | ca | |

| ISO 639-2 | cat | |

| ISO 639-3 | either: cat – Catalan cat – Valencian |

|

| Linguasphere | ||

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Catalan (English pronunciation: /kætəˈlæn, ˈkætəlæn, ˈkætələn/[1]; Catalan: català, pronounced [kətəˈɫa] or [kataˈla]) is a Romance language, the national and the only official language of Andorra, and a co-official language in the Spanish autonomous communities of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Valencian Community, where it is known as Valencià (Valencian), as well as in the city of Alghero on the Italian island of Sardinia. It is also spoken, with no official recognition, in the autonomous communities of Aragon (in La Franja) and Murcia (in Carche) in Spain, and in the historic Roussillon region of southern France, roughly equivalent to the current département of the Pyrénées-Orientales (Northern Catalonia).

Although recognized as a regional language of the Région Pyrénées-Orientales [2] since 2007, Catalan has no real official recognition as French is still the only official language in France, according to the French Constitution of 1958.[3]

Contents |

History

The Catalan language developed from Vulgar Latin on both sides of the eastern part of the Pyrenees mountains (counties of Rosselló, Empúries, Besalú, Cerdanya, Urgell, Pallars and Ribagorça). It shares features with Gallo-Romance, Ibero-Romance, and the Gallo-Italian speech types of Northern Italy. Though some hypothesize a historical split from languages of Occitan typology, the entire area running from Liguria on the present Italian coast to at least Alicante in Spain is more scientifically viewed as a classic dialect continuum, with some eventual perturbation as a result of political divisions and overlay of standard national languages.

As a consequence of the Aragonese and Catalan conquests from Al-Andalus to the south and to the west, it spread to all present-day Catalonia, Balearic Islands and most of Valencian Community.

During the 15th century, during the Valencian Golden Age, the Catalan language reached its highest cultural splendor, which was not matched again until La Renaixença, 4 centuries later.

After the Treaty of the Pyrenees, a royal decree by Louis XIV of France on 2 April 1700 prohibited the use of Catalan language in present-day Northern Catalonia in all official documents under the threat of being invalidated.[4] Since then, the Catalan language has lacked official status in the Catalan-speaking region in France.

On 10 December 2007, the General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales officially recognized the Catalan language as one of the languages of the department in the ARTICLE 1 (a) of its Charte en faveur du Catalan[5] (b), and seek to further promote it in public life and education.

(a) «ARTICLE 1 : The General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales officially recognizes, beside the French language, the Catalan as language of the department. (Le Conseil Général des Pyrénées-Orientales reconnaît officiellement, au côté de la langue française, le catalan comme langue du département.')»

(b) Carta a favor del Català[6]

- See also Language policy in France

After the Nueva Planta Decrees, administrative use and education in Catalan was also banned in the territories of the Spanish Kingdom. It was not until the Renaixença that use of the Catalan language started to recover.

In Francoist Spain (1939–1975), the use of Spanish in place of Catalan was promoted, and public use of Catalan was discouraged by official propaganda campaigns. The use of Catalan in government-run institutions and in public events was banned. During later stages of the Francoist regime, certain folkloric or religious celebrations in Catalan were resumed and tolerated. Use of Catalan in the mass media was forbidden, but was permitted from the early 1950s[7] in the theatre. Publishing in Catalan continued throughout the dictatorship.[8] There was no official prohibition of speaking Catalan in public or in commerce, but all advertising and signage had to be in Spanish alone, as did all written communication in business.[9]

Following the death of Franco in 1975 and the restoration of democracy, the use of Catalan increased partly because of new affirmative action and subsidy policies and the Catalan language is now used in politics, education and the Catalan media, including the newspapers Avui ("Today"), El Punt ("The Point") and El Periódico de Catalunya (sharing content with its Spanish release and with El Periòdic d'Andorra, printed in Andorra); and the television channels of Televisió de Catalunya (TVC): TV3, the main channel, and Canal 33/K3 (culture and cartoons channel) as well as a 24-hour news channel 3/24 and the TV series channel 300; in València Canal 9, 24/9 and Punt 2; in the Balearic islands IB3; there are also many local channels available in region in Catalan, such as BTV and 8TV (in the metropolitan area of Barcelona), Barça TV, Canal L'Hospitalet (L'Hospitalet de Llobregat), Canal Terrassa (Terrassa), Televisió de Sant Cugat TDSC (Sant Cugat del Vallès), Gandia Televisió (Gandia, Valencian Country), Televisió de Mataró TVM (Mataró) and Catalan-dubbed television programs.

The number of persons fluent in Catalan varies depending on the sources used. The 2004 language study cited below in this article does not indicate the total number of speakers, but an estimate of 9-9.5 million can be made, by matching the percentage of speakers to the population of each area where Catalan is spoken ("Sociolinguistic Situation in Catalan-speaking Areas." cited in the Section, External Links, of this article) The web site of the Generalitat gives the number as of June 2007 as 9,118,882 speakers of Catalan.

Classification

The ascription of Catalan to the Occitano-Romance branch of Gallo-Romance languages is not shared by all linguists. According to the Ethnologue, its specific classification is as follows:[10]

- Indo-European languages

- Italic languages

- Romance languages

- Italo-Western languages

- Western Italo-Western languages

- Gallo-Iberian languages

- Ibero-Romance languages

- East Iberian languages

- Ibero-Romance languages

- Gallo-Iberian languages

- Western Italo-Western languages

- Italo-Western languages

- Romance languages

- Italic languages

Catalan bears varying degrees of similarity to languages subsumed under the cover term Occitan. (See also Occitan language: Differences between Occitan and Catalan and Gallo-Romance languages.) As would be expected of closely cognate languages, Catalan also shares numerous features with other Romance languages, with similarities generally decreasing with physical distance.

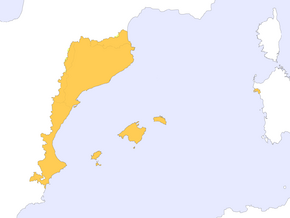

Geographic distribution

Catalan is spoken in:

- Catalonia (Catalunya), in Spain.

- Most of the Valencian Community (Comunitat Valenciana), in Spain, where it is called Valencian.

- An adjacent strip (La Franja) of Aragon, Spain, in particular the comarques of Ribagorça, Llitera, Baix Cinca, and Matarranya.

- Balearic Islands (Illes Balears i Pitiüses), in Spain.

- Andorra (Principat d'Andorra).

- Northern Catalonia (Catalunya Nord : name used officially for the first time on 10 December 2007 by the General Council of the Pyrénées-Orientales), in France.

- The city of Alghero (l'Alguer) in Sardinia, Italy.

- A small region in Murcia, Spain, known as Carche (El Carxe in Catalan).

All these areas are referred to by some as Catalan Countries (Catalan: Països Catalans), a denomination based on cultural affinity and common heritage, that has also had a subsequent political interpretation but no official status.

Number of Catalan speakers

Territories where Catalan is official (or co-official)

| Region | Understands [11] | Can speak [11] |

| Catalonia (Spain) | 6,502,880 | 5,698,400 |

| Balearic Islands (Spain) | 852,780 | 706,065 |

| Valencian Community (as Valencian) (Spain) | 3,448,780 | 2,407,951 |

| Andorra | 75,407 | 61,975 |

| Northern Catalonia (France) | 203,121 | 125,621 |

| TOTAL | 11,082,968 | 9,000,012 |

Figures relate to all self-declared capable speakers, not just native speakers.

Other territories

| Region | Understands [11] | Can speak [11] |

| Alguer (Sardinia, Italy) | 20,000 | 17,625 |

| Franja de Ponent | 47,250 | 45,000 |

| El Carxe (Murcia) | No data | No data |

| Rest of World | No data | 350,000 |

| TOTAL | 417,250 | 412,625 |

Figures relate to all self-declared capable speakers, not just native speakers.

World

| Region | Understands [11] | Can speak [11] |

| Catalan-speaking territories (Europe) | 11,082,968 | 9,000,621 |

| Rest of World | No data | 350,000 |

| TOTAL | 11,082,968 | 9,412,637 |

Notes: The number of people who understand Catalan includes those who can speak it.

Dialects

Eastern dialects:

█ Northern Catalan

█ Central Catalan

█ Balearic and Alguerese

Western dialects:

█ North-Western Catalan

█ Valencian

In 1861, Manuel Milà i Fontanals proposed a division of Catalan into two major dialect blocks: Eastern Catalan and Western Catalan. The different Catalan dialects show deep differences in lexicon, grammar, morphology and pronunciation due to historical isolation. Each dialect also encompasses several regional varieties.

There is no precise linguistic border between one dialect and another because there is nearly always a transition zone of some size between pairs of geographically separated dialects (except for dialects specific to an island). The main difference between the two blocks is their treatment of unstressed vowels, in addition to a few other features:

- Western Catalan (Bloc o Branca del Català Occidental):

- Unstressed vowels: [a e i o u]. Distinctions between e and a and o and u.

- Initial or post-consonantal x is an affricate /tʃ/ (there are exceptions in Xàtiva, xarxa, Xavier, xenofòbia... these are pronounced with /ʃ/). Between vowels or when final and preceded by i, it is /jʃ/.

- 1st person present indicative is -e or -o.

- Latin long /eː/ and short /i/ have become /e/.

- Inchoative verbs in -ix, -ixen, -isca

- Maintenance of medieval nasal plural in proparoxytone words: hòmens, jóvens

- Specific vocabulary: espill, xiquet, granera, melic...

- Eastern Catalan (Bloc o Branca del Català Oriental):

- The vowels /e/, /ɛ/ and /a/ become /ə/ when unstressed, and /o/, /ɔ/ and /u/ become [u].

- Initial or post-consonantal x is the fricative /ʃ/. Between vowels or when final and preceded by i it is also /ʃ/.

- 1st person present indicative is -o, -i or there is no marker.

- Latin long /eː/ and short /i/ have become /ɛ/ (In most of Balearic Catalan they are pronounced [ə] and in Alguerese [e]).

- Inchoative verbs in -eix, -eixen, -eixi.

- The -n- of medieval nasal plural is dropped in proparoxytone words: homes, joves.

- Specific Vocabulary: mirall, noi, escombra, llombrígol...

In addition, neither dialect is completely homogeneous: any dialect can be subdivided into several sub-dialects. Catalan can be subdivided into two major dialect blocks and those blocks into individual dialects:

|

Western Catalan

|

Eastern Catalan

|

Standards

There are two main standards for Catalan language, one regulated by the Institut d'Estudis Catalans (IEC), general standard, with Pompeu Fabra's orthography as axis, keeping features from Central Catalan, and the other regulated by the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL), restricted scale standard, focused on Valencian standardization on the basis of Normes de Castelló, that is, Pompeu Fabra's orthography but more adapted to Western Catalan pronunciation and features of Valencian dialects.

IEC's Standard, apart from the basis of Central Catalan features, takes also other dialects features considering as standard. Despite this, the most notable difference between both standards is some tonic "e" accentuation, for instance: francès, anglès (IEC) - francés, anglés (AVL) (French, English), cafè (IEC) - café (AVL) (coffee), conèixer (IEC) - conéixer (to know), comprèn (IEC) - comprén (AVL) (he understands). This is because of the different pronunciation of some tonic "e", especially tonic Ē (long "e") and Ǐ (breves "i") from Latin, in both Catalan blocks ([ɛ] in Eastern Catalan and [e] in Western Catalan). Despite this, AVL's standard keeps grave accent "è", without pronouncing this "e" [ɛ], in some words like: què (what), València, èter (ether), sèsam (sesame), sèrie (series) and època (age).

There are also some other divergences like the 'tl use by AVL in some words instead of tll like in ametla/ametlla (almond), espatla/espatlla (back) or butla/butlla (bull), the use of elided demonstratives (este this, eixe that (near)) in the same level as reinforced ones (aquest, aqueix) or the use of many verbal forms common in Valencian, and some of these common in the rest of Western Catalan too, like subjunctive mood or inchoative conjugation in -ix- at the same level as -eix- or the priority use of -e morpheme in 1st person singular in present indicative (-ar verbs): "jo compre" (I buy) instead of "jo compro".

In Balearic Islands, IEC's standard is used but adapted into Balearic dialect by the University of the Balearic Islands's philological section, Govern de les Illes Balears's consultative organ. In this way, for instance, IEC says it is correct writing "cantam" as much as "cantem" (we sing) but the University says that the priority form in the Balearic Islands must be "cantam" in all fields. Another feature of the Balearic standard is the non-ending in the 1st person singular present indicative: "jo cant" (I sing), "jo tem" (I fear), "jo dorm" (I sleep).

In Alghero, the IEC has adapted its standard to the Alguerese dialect. In this standard one can find, among other features: the definite article lo instead of el, special possessive pronouns and determinants la mia (mine), lo sou/la sua (his/her), lo tou/la tua (yours), and so on, the use of -v- in the imperfect tense in all conjugations: cantava, creixiva, llegiva; the use of many archaic words, usual words in Alguerese: manco instead of menys (less), calqui u instead of algú (someone), qual/quala instead of quin/quina (which), and so on; and the adaptation of weak pronouns.

Status of Valencian

The official language academy of the Valencian Community (the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua) considers Catalan and Valencian simply to be two names for the same language.[12] All universities teaching Romance languages, and virtually all linguists, consider these two to be linguistic variants of the same language (similar to Canadian French versus Metropolitan French, and European versus Brazilian Portuguese).

There is a roughly continuous set of dialects covering the various regional forms of Catalan/Valencian, with no break at the border between Catalonia and the Valencian Community, and the various forms of Catalan and Valencian are mutually intelligible even between the most eastern and western varieties. This is not to say that there are no differences between the two and the speech of Valencians is recognizable both in pronunciation as well as in morphological and lexical peculiarities. However, these differences are not any wider than among North-Western Catalan and Eastern Catalan. In fact, Northern Valencian (spoken in the Castelló province and Matarranya valley, a strip of Aragon) is more similar to the Catalan of the lower Ebro basin (spoken in southern half of Tarragona province and another strip of Aragon) than to apitxat Valencian (spoken in the area of L'Horta, in the province of Valencia).

What gets called a language (as opposed to a dialect) is defined partly by mutual comprehensibility as well as political and cultural factors. In this case, the perceived status of Valencian as a dialect of Catalan has historically had important political implications including Catalan nationalism and the idea of the Països Catalans or Catalan countries. Arguing that Valencian is a separate language may sometimes be part of an effort by Valencians to resist a perceived Catalan nationalist agenda aimed at incorporating Valencians into what they feel is a "constructed" nationality centered around Barcelona. As such, the issue of whether Catalan and Valencian constitute different languages or merely dialects has been the subject of political agitation several times since the end of the Franco era. The latest political controversy regarding Valencian occurred on the occasion of the drafting of the European Constitution in 2004. The Spanish government supplied the EU with translations of the text into Basque, Galician, Catalan, and Valencian, but the Catalan and Valencian versions were identical.[13] While professing the unity of the Catalan language, the Spanish government claimed to be constitutionally bound to produce distinct Catalan and Valencian versions because the Statute of Autonomy of the Valencian Community refers to the language as Valencian. In practice, the Catalan, Valencian, and Balearic versions of the EU constitution are identical: the government of Catalonia accepted the Valencian translation without any changes under the premise that the Valencian standard is accepted by the norms set forth by the IEC.

Catalan may be seen instead as a multi-centric language (much like English); there exist two standards, one for Oriental Catalan, regulated by the IEC, which is centered around Central Catalan (with slight variations to include Balearic verb inflection) and one for Occidental, regulated by the AVL, centered around Valencian.

The AVL accepts the conventions set forth in the Normes de Castelló as the normative spelling, shared with the IEC that allows for the diverse idiosyncrasies of the different language dialects and varieties. As the normative spelling, these conventions are used in education, and most contemporary Valencian writers make use of them. Nonetheless, a small minority mainly of those who advocate for the recognition of Valencian as a separate language, use in a non-normative manner an alternative spelling convention known as the Normes del Puig.

Sounds and writing system

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | (c) ~ k | ||

| voiced | b | d | (ɟ) ~ ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | (ts) | (tʃ) | |||

| voiced | (dz) | (dʒ) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | (v) | z | ʒ | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||

| Approximant | j | w | ||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||

Grammar

The first descriptive and normative grammar book of modern Catalan was written by Pompeu Fabra in 1918. In 1995 a new grammar by Antoni M. Badía i Margarit was published, which also documents the Valencian and Balearic varieties.

The grammar of Catalan mostly follows the general pattern of Western Romance languages.

Substantives and adjectives are not declined by case, as in Classical Latin. There are two grammatical genders—masculine and feminine.

Grammatical articles originally developed from Latin demonstratives. The actual form of the article depends on the gender and the number and the first sounds of the word and can be combined with prepositions that precede them. A unique feature of Catalan is a definite article that may precede personal names in certain contexts. Its basic form is en and it can change according to its environment (the word "en" has also other lexical meanings). One of the common usages of this article is in the word can, a combination of "la casa" shortened to ca (house) and en, which here means "the". For example "la casa d'en Sergi" becomes "Can Sergi" meaning "the house of Sergi", "Sergi's house".

Verbs are conjugated according to tense and mood similarly to other Western Romance languages—present and simple preterite are based on classical Latin, future is formed from infinitive followed by the present form of the auxiliary verb haver (written together and not considered periphrastic), and periphrastic tenses are formed from the conjugated auxiliary verbs haver (to have) and ésser (to be) followed by the past participle. A unique tense in Catalan is the periphrastic simple preterite, which is formed of "vaig", "vas" (or "vares"), "va", "vam" (or "vàrem"), "vau" (or "vàreu") and "van" (there is the usual wrong idea these forms are the conjugated forms of "anar", which means "to go"), which is followed by the infinitive of the verb. Thus, "Jo vaig parlar" (or more simply "Vaig parlar") means "I spoke".

Nominative pronouns are often omitted, as the person can be usually derived from the conjugated verb. The Catalan rules for combination of the object pronoun clitics with verbs, articles and other pronouns are significantly more complex than in most other Romance languages; see Weak pronouns in Catalan.

Catalan names

Catalan naming customs are similar to those of Spain; a person receives two last names—their father's and their mother's. The two last names are usually separated by the particle "i", meaning "and". (In Spanish the equivalent particle is written y, but often omitted altogether.)

For example, the full name of the architect Antoni Gaudí is Antoni Gaudí i Cornet after his parents: Francesc Gaudí i Serra and Antònia Cornet i Bertran, meaning he was son of Gaudí and Cornet.

Examples

Some phrases in the Central dialect -Barcelona and outskirts-:

- Catalan: català [kətəˈɫa]

- Hello: hola [ˈɔɫə]

- Good-bye: adéu [əˈðew]; adéu-siau [əˈðew siˈaw]; siau [siˈaw]; 'déu [ˈdew] (colloquial use)

- Please: si us plau or sisplau [sisˈpɫaw]; per favor [ˈpəɾ fəˈβoɾ]

- Thank you: gràcies [ˈɡɾasiəs]; mercès [məɾˈsɛs]; merci [ˈmɛɾsi] (colloquial use)

- Sorry: perdó [pəɾˈðo], em sap greu [əmsabˈɡɾew]; ho sento [uˈsentu]

- This one: aquest [əˈkɛt] (masc.); aquesta [əˈkɛstə] (fem.)

- How much?: quant val? [ˈkwamˈbaɫ]; quant és? [ˈkwanˈtes]

- Yes: sí [ˈsi]

- No: no [ˈno]

- I don't understand (it): no ho entenc [ˈnowənˈteŋ]

- Where's the bathroom?: On és el bany? [ˈoˈnezəɫˈβaɲ]; On és el lavabo? [ˈoˈnezəɫɫəˈβaβu]; On és el servei? [ˈoˈnezəɫsəɾˈβɛj]

- Generic toast: salut! [səˈɫut];

- Bless you! (after sneezing): Jesús [ʒəˈzus]; salut! [səˈɫut]

- Do you speak Catalan? (informal singular, addressing as tu using 2nd person singular): Que parles català? [kəˈpaɾɫəs kətəˈɫa]

- Do you speak Catalan? (formal singular, addressing as vostè using 3rd person singular): Que parla català? [kəˈpaɾɫə kətəˈɫa]

- Do you speak Catalan? (informal plural, addressing as vosaltres using 2nd person plural): Que parleu català? [kəpəɾˈɫɛw kətəˈɫa]

- Do you speak Catalan? (formal plural, addressing as vostès using 3rd person plural): Que parlen català? [kəˈpaɾɫən kətəˈɫa]

The same phrases pronounced as in the standard Valencian:

- Valencian: valencià [valensiˈa]

- Hello: hola [ˈɔla]

- Good-bye: adéu [aˈðew]

- Please: per favor [peɾ faˈvoɾ]

- Thank you: gràcies [ˈɡɾasies]

- Sorry: perdó [peɾˈðo]; ; ho sent [uˈsent] or [uˈseŋk]

- This one: este [ˈeste] (masc.); esta [ˈesta] (fem.)

- How much?: quant val? [ˈkwaɱˈvaɫ]; quant és? [ˈkwanˈtes]

- Yes: sí [ˈsi]

- No: no [ˈno]

- I don't understand: no ho entenc [ˈnowanˈteŋ]

- Where's the bathroom?: on és el bany? [oˈnezeɫˈβaɲ]

- Generic toast: salut! [saˈlut]

- Bless you! (after sneezing): Jesús! [dʒeˈzus]; salut! [saˈlut]

- Do you speak Valencian?: parles valencià? [ˈpaɾlez valensiˈa]

Learning Catalan

- Digui, digui... Curs de català per a estrangers. A Catalan Handbook. — Alan Yates and Toni Ibarz. — Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Cultura, 1993. -- ISBN 84-393-2579-7.

- Teach Yourself Catalan. — Alan Yates. — McGraw-Hill, 1993. — ISBN 0340194995.

- Colloquial Catalan. — Toni Ibarz and Alexander Ibarz. — Routledge, 2005. — ISBN 0-415-23412-3.

- speakcat On-line basic course http://intercat.cesca.es/speakcat/

- Parla.Cat The Official free on-line complete course http://www.parla.cat

- Catalan Grammar.— Joan Gili.— Dolphin Book Company (Oxford: 1993).— ISBN 0852150784.

Catalan courses are offered at a number of universities in Europe and North America.

Voluntaris per la Llengua is a Catalan language learning programme.

English words of Catalan origin

- Aioli, from all i oli, a typical sauce made by mixing olive oil and garlic with a mortar and pestle.

- Aubergine, from Catalan albergínia[15] through French

- Barracks, from Old Catalan barraca (hut) through French baraque.[16] Another term Barracoon, from Catalan barraca (hut) through Spanish barracón.[16]

- Surge, from Middle French, which took it from Old Catalan surgir[15]

- Paella, Valencian Catalan, via Old French paele, ultimately from Latin patella (small dish)[15]

See also

- Catalan orthography

- Institut d'Estudis Catalans (Catalan Studies Institute)

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (Valencian Academy of the Language)

- Pompeu Fabra

- Catalan literature

- Languages of France

- Languages of Italy

- Languages of Spain

- Names of Catalan language

- Catalan names

- .cat - The first top-level domain based on language and culture

- Alguerese

- Balearic

- Valencian

- Spanish (Spain) keyboard layout, used to type Catalan

- Òmnium Cultural

- Plataforma per la Llengua

References

- ↑ Catalan. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Catalan (accessed: March 20, 2010).

- ↑ Charte en faveur du Catalan

- ↑ French Constitution, 1958: Article 2. The language of the Republic shall be French.

- ↑ L'interdiction de la langue catalane en Roussillon par Louis XIV; taken from the website "CRDP de l'académie de Montpellier"

- ↑ "Charte en faveur du Catalan". Cg66.fr. 2004-07-28. http://www.cg66.fr/culture/patrimoine_catalanite/catalanite/charte.html. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Carta a favor de la llengua i la cultura catalanes". Cg66.fr. 2004-07-28. http://www.cg66.fr/culture/patrimoine_catalanite/catalanite/index.html. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ Marc Howard Ross, "Cultural Contestation in Ethnic Conflict", page 139. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ↑ The Resurgence of Catalan Earl W. Thomas Hispania, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Mar., 1962), pp. 43–48 doi:10.2307/337523

- ↑ Orden del Excmo. Sr. Gobernador Civil de Barcelona. EL USO DEL IDIOMA NACIONAL EN TODOS LOS SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS. 1940.

- ↑ "Ethnologue Report". Ethnologue.com. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=cat. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Sources:

- Catalonia: Statistic data of 2001 census, from Institut d'Estadística de Catalunya, Generalitat de Catalunya [1].

- Land of Valencia: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Valencià d'Estadística, Generalitat Valenciana [2].

- Land of Valencia: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Valencià d'Estadística, Generalitat Valenciana [3].

- Balearic Islands: Statistical data from 2001 census, from Institut Balear d'Estadística, Govern de les Illes Balears [4].

- Northern Catalonia: Media Pluriel Survey commissioned by Prefecture of Languedoc-Roussillon Region done in October 1997 and published in January 1998 [5].

- Andorra: Sociolinguistic data from Andorran Government, 1999.

- Aragon: Sociolinguistic data from Euromosaic [6].

- Alguer: Sociolinguistic data from Euromosaic [7].

- Rest of World: Estimate for 1999 by the Federació d'Entitats Catalanes outside the Catalan Countries.

- ↑ Dictamen de l'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua sobre els principis i criteris per a la defensa de la denominació i l'entitat del valencià - Report from Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua about denomination and identity of Valencian.

- ↑ Isabel I Vilar, Ferran. “Traducció única de la Constitució europea.” I-Zefir. 30 Oct. 2004. 29 Apr. 2009 <http://www.mail-archive.com/infozefir@listserv.rediris.es/msg00442.html>.

- ↑ Carbonell, Joan F.; Llisterri, Joaquim (1999), "Catalan", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the usage of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 61–65, ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Philip Babcock Gove, ed (1993). Webster's Third New International Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, inc.. ISBN 3-8290-5292-8.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers. 1991. ISBN 0-00-433286-5.

- Wheeler, Max; Yates, Alan; Dols, Nicolau (1999), Catalan: A Comprehensive Grammar, London: Routledge

External links

- Sociolinguistic situation in Catalan-speaking areas. Tables. Official data about sociolinguistic situation in Catalan-speaking areas: Catalonia (2003), Andorra (2004), the Balearic Islands (2004), Aragonese Border (2004), Northern Catalonia (2004), Alghero (2004) and Valencia (2004).

Institutions

- Institut d'Estudis Catalans

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua

- Secretaria de Política Lingüística de la Generalitat de Catalunya

About the Catalan language

- Ethnologue report for Catalan

- GRAMÀTICA CATALANA A Catalan grammar

Monolingual dictionaries

- Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana from the Institut d'Estudis Catalans

- Gran Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana from Enciclopèdia Catalana

- Diccionari Català-Valencià-Balear d'Alcover i Moll

- Diccionari valencià online

- Diccionari Invers de la Llengua Catalana Dictionary of Catalan words spelled backwards

Bilingual and multilingual dictionaries

- Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana Multilingüe from Enciclopèdia Catalana (Catalan < > Spanish, English, French and German)

- DACCO. Open source, collaborative dictionary (Catalan < > English)

- Dictionary from Webster's Online Dictionary - The Rosetta Edition (Catalan < > English)

- Catalan-English-Catalan dictionary

Automated translation systems

- Traductor Automated, on-line translations of text and web pages (Catalan < > English, French and Spanish)

- SisHiTra Automated, on-line translations of text and web pages (Catalan < > Spanish)

- apertium.org – Apertium (free software) translates text, documents or web pages, on-line or off-line, between Catalan and English, Aranese, Spanish, French, Occitan, Portuguese and Esperanto

Phrasebooks

- Catalan phrasebook on Wikitravel

Learning resources

- Learn Catalan Online with Volunteers

- Interc@t, set of electronic resources for learning the Catalan language and culture

- Learn Catalan!, an introduction for the Catalonia-bound traveler

- On-line Catalan resources

- parla.cat

Catalan-language online encyclopedia

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||